Blind Bombing

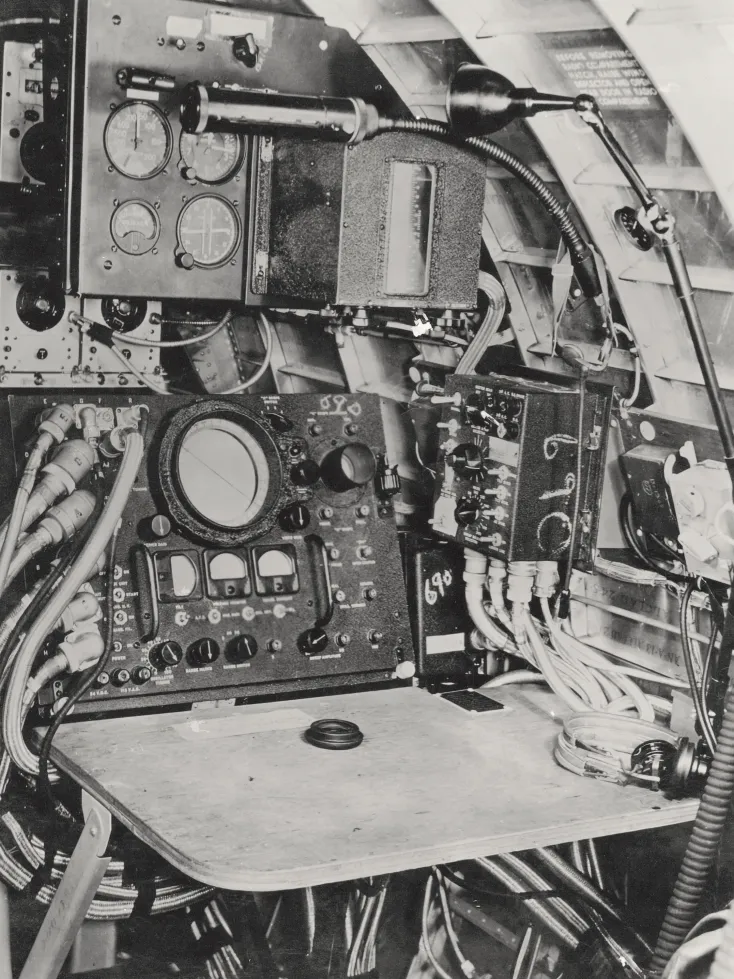

How Microwave Radar Brought the Allies to D-Day and Victory in World War II

By Norman Fine

Published 2019 by Potomac Books

National Prize Winner, 2020 IPPY Awards

About the Book

History, “reading like a detective story…”

(Nick Kotz, Pulitzer Prize winner for National Reporting)

The Unknown Story of the Secret Invention that won the Battle of the Atlantic and went on to Rescue D-Day

Blind Bombing, the silver medal winner in World History in the national 2020 IPPY Awards, is “a riveting addition to the literature on scientific innovation during the Second World War” (Kirkus Reviews). We’ve all read about other technical wartime achievements − breaking Germany’s Enigma codes and the development of the atomic bomb. Here’s the thrilling story of the top-secret invention that conquered the two primary obstacles to D-Day. Unknown to Axis forces, the invention went on from D-Day to be used by every Allied military force on the ground, in the air, and on the seas both in the Atlantic and the Pacific theaters. It was the single invention most influential in the winning of the war, and most historians writing for a general readership have simply ignored it.

“To completely understand the Allied victory in World War II, read Norman Fine’s new book.” (The Honorable G. Philip Hughes, Senior Vice President, Council of American Ambassadors).

Praise for Blind Bombing

Silver Medalist in World History2020 Independent Publishers Book Awards (IPPY)

Winner of the silver medal for World History in the 2020 Independent Publisher Book Awards, Fine’s book captures the technological innovation and inventions that changed the very nature of combat.

About the Author

With Norman Fine

Norman Fine is a retired electronics engineer, founder of a high-tech company, editor and publisher of an annual engineering design guide series in the 1990s, and author of four books and hundreds of articles on horse sport published in the U.S. and Britain.

From the Blog

How MIT’s Rad Lab rescued D-Day

Eighth Air Force News Article

Purchase Your Copy of Blind Bombing Today!

Immerse yourself in the rich and complete history of how Microwave Radar won the Battle of the Atlantic and rescued D-Day.

Blind Bombing is Fine’s thoughtful and thoroughly researched piece on the development of an overlooked invention that helped save Britain, then set the stage for D-Day in just five months. This book should be on the bucket list of anyone interested in understanding how World War II was won.